What is Contemporary Mysticism?

A dialogue between Hannes Schumacher and Glenn Wallis

HS: Does it exist at all? If not, what are we gonna talk about? For time immemorial, mysticism all around the world has been the most heretical theory and practice, a danger to all good and common sense, censored by the atheist no less than by the Pope. While the mystic in the past was constantly at risk to be beheaded, hanged or burned alive, nowadays, at least, mysticism is belittled as a historical curiosity and systematically excluded from the treasure room of academia. Could this be the right time for mysticism to eventually speak up, for the great mysteries to be revealed—to make a joke—given that it still exists?

The question “What is contemporary mysticism?” is not a matter of ontology but a speculative provocation summoning the hidden forces of the earth—rather a vision than a fact. In any case, the question doesn’t ask what contemporary mysticism “truly is,” but rather what it does. Shall we begin by juxtaposing mysticism with its contemporary versions? Or shall we jump immediately into the matter?

GW: I agree that the task of a conversation about “contemporary mysticism” necessarily concerns the “speculative provocation” that you mention. I really like that formulation. I think it captures the fact that wresting the word “mysticism” from the ancient heretical discourse that you refer to will be difficult—and fraught.

A specific discourse called “contemporary mysticism” does exist. But in every case that I know of (and I have been following this discourse for decades now), it is a continuation of the one from “times immemorial,” as you put it. This contemporary mysticism even takes pride in the fact that it still speaks the language of the old mystics: union with God; purification of the soul; the ladder of divinity, and so on. Contemporary mysticism sometimes modernizes (and indeed somewhat secularizes) this language as, for example (actual book titles), “living mindfully in the universe,” “angelic mysticism,” “fusing with the radiant heart of the cosmos.” So, for people who seek mystical discourse and practice as a “speculative provocation,” contemporary mysticism registers as but a pale husk of a once majestic being.

Why were those old mystics beheaded, hanged, and burned alive? One reason was because their teachings presented a potentially devastating challenge to the status quo. The status quo—the state-church-social nexus—desired to keep the individual dependent on it, on the status quo. The mystic revealed a hidden way, a way that does not traverse the institutions of authority.

In circumventing the authorities, mysticism in effect negates their existence. Imagine what would become of Christianity, for example, if it embraced Meister Eckhart’s assertion that “the just and godly person created heaven and earth, together with God,” and that “such a person is the creator of the eternal word, and without such a person God would not know what to do.” God would not know what to do! Wow! What are the personal, social, and political implications?

In my estimation, contemporary mysticism is the polar opposite of the provocation you invoke. Its practice and ideology are arguably in perfect harmony with the machinations of authority today—from the dictates of everyday social morality and the institutions of state and religion, to the omnipresent tentacles of neoliberal capitalism. In fact, to my eyes, contemporary mysticism is a staunch ally to the very forces of personal and collective oppression that someone like Marguerite Porete, the author of The Mirror of Simple Souls, sacrificed her life to resist.

I look forward to exploring your contention that the question for us is not what is contemporary mysticism, but rather what does—or might—it do? It might be useful for our dialogue to say something about the joke you make. Like most good jokes, it contains much truth. Just for future reference, here are two definitions that continue to define our understanding of the noun mysticism. The first definition captures something of the insider’s view and the second, the outsider’s.

1. Mysticism: mystical theology; belief in the possibility of union with or absorption into God by means of contemplation and self-surrender; belief in or devotion to the spiritual apprehension of truths inaccessible to the intellect.

2. Mysticism: religious belief that is characterized by vague, obscure, or confused spirituality; a belief system based on the assumption of occult forces, mysterious supernatural agencies, etc. (Oxford English Dictionary)

In the spirit of “speculative provocation,” I will end my initial remarks with a quote from a thinker whom I will probably refer to often in our dialogue, François Laruelle: “Deprived of spiritualism, drained of idealism, the subject of [contemporary] mysticism is a furious utopian.”

The Chatter of a Beggar’s Teeth

HS: Thanks for your critical remarks, I think they will be fruitful as to specify the question in regard, and perhaps the answer, if there is one. “Mysticism” is a term I like because, at least to me, it radically departs from contemporary trends of “spirituality” or “esotericism,” not least from the “occult” or “magic”. Simply let’s provoke and say: the kind of mysticism that I’d like to talk about is able to resist the capture of the machinations of authority you mentioned. How could this be possible?

As you know, the Indian schools of thought are commonly categorized as orthodox (āstika) and heterodox (nāstika) and we may expand this to a global scale: atheism vs. theism, for example. Mysticism, in my view, is always in between these two extremes, questioning not only the orthodoxy but also its straight opposite: it is against but not opposed; everywhere it is an immanent critique. The kind of mysticism that I’d like to talk about is paradox, uncategorized, ungraspable. That’s why it came to ask itself whether it exists at all.

Perhaps we could start by illustrating some examples of the past and see what they might mean for us today. The negative theology of Pseudo Dionysios, Nicholas of Cusa and many others in the West and in the East, confronts the so-called via positiva—narrative accounts of God—with the via negativa: Since the infinitude of God can only be approximated by analogy with finite beings, negative theology, instead, negates all attributes of God, who is eventually envisioned as a dark cloud of unknowing. In order not to contradict themselves, these negations have to be a simple No rather than determinate or logical negations. The only problem is that negative theology, between the lines, would still insist on an unquestionable essence of God which can merely not be grasped by the limited minds of human beings. For contemporary mysticism, instead, the absolute has no essence in itself, thus foreclosing any speculation about God, once and for all.

Seen from the inside, there is nothing “mysterious” about mysticism; it only understands the mystical as the mystical, that is: there’s nothing hiding in that cloud.

To give a similar example from the Kabbalah, Rabbi Mendel of Rymanov states that when Moses climbed Mount Sinai to receive the Ten Commandments, all that the people of Israel could hear directly from God was the throat sound of aleph which in the Hebrew text forms the very beginning of the first Commandment, the aleph of the word anokhi, meaning ‘I.’ As Gershom Scholem notes:

To hear the aleph is to hear next to nothing; it is the preparation for all audible language, but in itself conveys no determinate, specific meaning. Thus, with his daring statement that the actual revelation to Israel consisted only of the aleph, Rabbi Mendel transformed the revelation on Mount Sinai into a mystical revelation, pregnant with infinite meaning, but without specific meaning. In order to become a foundation of religious authority, it had to be translated into human language, and that is what Moses did.

And how about this Moses? Did he not also only hear this aleph and “interpreted” it the way it pleased him? In Arnold Schönberg’s opera Moses and Aaron, the story takes a different turn. Here Moses is the one who is hopelessly resisting the machinations of authority instantiated by his brother Aaron. At the end of the opera, Moses exclaims: “Oh word, you word, that I lack!” (O Wort, du Wort, das mir fehlt!). This “lack” of words is the last trace of authority in Schönberg’s Moses.

As in my previous example about the cloud, the aleph does not “lack” a meaning but is simply meaningless, just as the absolute has no essence in itself: it is only us humans who endow it with a hidden meaning. And still: to hear the aleph thundering is not to hear nothing but “next to nothing”—a roaring orchestra, my friend! Although it is devoid of a “specific meaning,” it is “pregnant with infinite meaning.” If you try to grasp it, it escapes. Who would have guessed that something like a law could sprout from that?

GW: I want to focus my response on your statement “The kind of mysticism that I’d like to talk about is paradox, uncategorized, ungraspable. That’s why it came to ask itself whether it exists at all.” To me, what you say here expresses “the mystical” proper. And I agree that it is far more interesting than what I would call “instrumental mysticism” or the mysticism of otherworldy transcendental attainment.

The illustrative examples that you give are, to me, examples of mystical speech. I almost want to say that they are such speech in the first instance (that is, eventually morphing into the quotidian). But the more I think about it, the more such speech appears to remain so. So, for instance, Scholem’s “To hear the aleph is to hear next to nothing” never exits from utterance pure and simple. A proposition: “The mystical” is a mode of speech. Maybe this is what you are pointing to when you say that “for contemporary mysticism the absolute has no essence in itself, thus foreclosing any speculation about God, once and for all,” and that “Seen from the inside, there is nothing ‘mysterious’ about mysticism; it only understands the mystical as the mystical, that is: there’s nothing hiding in that cloud.”

Understanding it as speech, however, I do want to take mysticism’s tropes and metaphors and imagery and so on, very seriously. So, the question, for me, then becomes: what might mysticism’s “cloud” imagery (for example) be about? In even broader terms, I would want to take seriously—as a signpost, so to speak—mysticism’s general rhetorical strategy. Why all this talk about clouds, empty essence, paths of negation, darkness, urchromia, namelessness impossibility, unknowing, words that fail, language that stumbles, falters, and disintegrates within the void? Why veils and initiations and secret teachings? Indeed, why this very talk about the mystical? Such speech is often poetically beautiful and always evocative. (Might this fact thus be a hint?) But what is it evoking? In other words, to invoke your original query: what does mysticism do?

In his two-volume work The Mystic Fable, Michel de Certeau shows that mystical speech arises out of social, historical, and psychological fragmentation and disintegration. What becomes of the speech of a laughing madman, an idiot woman, a troubled child, or a schizophrenic (Certeau’s examples, if I remember correctly)? Do they speak with the diction, rhythm, and articulation of fine, upstanding citizens? Of course not! Does their speech not bear traces of “the mystical”? Is it not virtually incomprehensible, dark, disturbed, distant, obscure, fragmentary? I think of Antonin Artaud’s statement that “All true language is incomprehensible, like the chatter of a beggar’s teeth.” Will such speech not echo that of the subject’s mental condition? And, even more crucially, will that mental condition not often be an echo of the subject’s social conditions? Consider that, serious cases of organic brain damage aside, labels like “mad” and “troubled” and so on, reflect more about the society that does the labeling than about any human subjectivity.

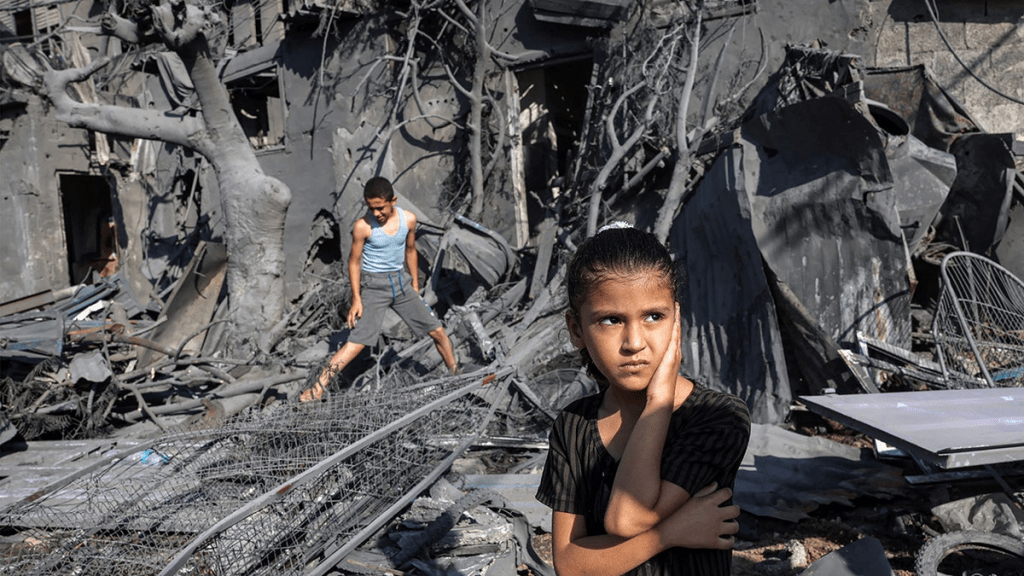

So, to bring my response to a close, I want to suggest that “mysticism” might be a way—a necessary and irreplaceable way—of speaking in a time of inconsolable collective mourning (as I believe we are currently, if not perpetually, in). In mourning, the platitudes and cliches and stock formulas that constitute the bulk of our “normal” everyday speech in supposedly “sane” times are rendered utterly meaningless, even cruel.

If contemporary mysticism is to be a path, I hope it will be not, like the ancient and medieval paths, pretend to lead toward some fantasized transcendental big Other but rather toward whatever it is mystical speech might be groping—chattering, stuttering—to bring into existence. A succinct way to put my point is: mysticism must be ruined—stripped of its otherworldly fragrance and saturated with the musty scent of earthly dirt.

Maybe an alternative title of our dialogue should be Mysticism in Ruins?

Chaos and Madness

HS: I agree that a discourse on “contemporary mysticism” must include an elaborate account of neurodiversity, and perhaps this is what it does. The phenomenon of madness in the past has been ambivalent between the two extremes of blasphemy and prophecy, nonsense and genius—but how on earth could you differentiate between an angel or a demon? On the other hand, today, madness is completely trivialized in terms of a so-called mental illness to be treated solely by professionals: psychotherapists and other gurus. How far have we gone that we rely on these authorities even in regard to our most intimate mental states! The great challenge that contemporary mysticism poses to us is a revaluation of madness, no longer as something trivial or numb, but as a revolutionary potential.

Since I participated in an ayahuasca ceremony in Ecuador, not a single day has passed in which I didn’t have a so-called mystical experience. But I also often ask myself, what is the actual difference between my altered state of consciousness and a proper schizophrenia? After all, I came to the conclusion that the only difference is the attitude toward one’s own condition: once it simply is a mental illness to be treated by professionals, once it is a synaesthetic hypersensitivity toward the chaos that surrounds us. And indeed, the whole point of ayahuasca as a so-called medicine, is to reconnect us with this wild and overwhelming nature from which we have been alienated in a long and coercive process of civilization. But to dive into this mystical adventure in the contemporary world while rejecting all authorities—even those of shamanic initiation—is to strip naked without help or any remedy. Every single day we live the whole creation of the world and the apocalypse, with all its details and its cruelty, and our only hope is the advice in the Book of Revelation: mē fobou, do not be afraid …

I also do agree that “mysticism must be ruined—stripped of its otherworldly fragrance.” However, I believe that there must still be a beyond—or rather down below—the plane of immanence which, yet, is not another world but utter chaos. What all these troubled children and madmen and madwomen are trying so hard to express is this very chaos they experience in the everyday, and to which the “civilized” have become so blind and deaf. These contemporary mystics are really messengers in the old sense of the word; the only difference is that they are not messengers of God but of chaos. And in a way we can say that it is chaos which expresses itself through them.

To dare a metaphysical statement, chaos is ontologically primordial in relation to logos. The Greek term ‘logos’ means language or speech but etymologically refers to a sorting out or collecting: the process of civilization. Chaos is primordial because, for the process of collection to take place, there must be something prior to be sorted out: “In the beginning was the word” (John 1:1) but “chaos came first” (Hesiod). However, the orthodoxy since time immemorial has been very keen to ban chaos from the magical circle of logos=God which turned out to be impossible. What we are witnessing today, is the inevitable return of chaos, and perhaps this is why the mystics never have been more important.

GW: I find your response here extremely moving. It itself is touched by the very “mystical” that I feel I am (we are?) groping toward. In the account that is coming into focus for me, this matter of mentality is massive. I would want to ascribe to any contemporary mysticism the essential characteristic of challenging our culturally preferred notion of “normality” over types of “neurodiversity.” I would even want to consider it a working axiom that, as you say, “perhaps this is what it does.” Many new problems and questions arise from this axiom, of course, but I feel that it is nonetheless a necessary point of departure.

If anyone balks at the suggestion that “madness” might entail “revolutionary potential,” a brief consideration from either side should give them pause. For example, from the side of “normalcy,” just consider the human-exacerbated disasters that attend our world—from large scale, long-term environmental degradation, to the creation of murderous political and economic systems, to dehumanizing ideological state apparatuses like schools and corporations, to the everyday alienation of our relations and lifestyles and the toxicity of our diets and our lived environments. From the other side, just consider the luminous visions of potential reality spun out by “deranged” visual artists, musicmakers, and storytellers. It is not mere Romantic hyperbole to claim that the particular derangement of certain kinds of art has the capacity to shake us from our deadening habituation by galvanizing and expanding our perspective of what is possible.

I also believe that another necessary axiom of any contemporary mysticism must be your “metaphysical statement” that “chaos is ontologically primordial in relation to logos.” Perhaps we can connect this “chaos axiom” to the “madness axiom” via a view like Adorno’s that “The darkening of the world makes the irrationality of art rational: radically darkened art.” Such a view reveals certain means through which we might, as you say, “reconnect with this wild and overwhelming nature from which we have been alienated in a long and coercive process of civilization.”

Anarchism, Art, Ecology

Whatever the means for such reconnection might be—the arts, ritualized hallucinogen consumption, maybe even Rimbaud-like contemplative derangement—however, I believe that it is necessary to extend the mystical beyond the level of mere individual lifestyle. So, a huge question that I have for a present or future mysticism is this: how we might not only create but sustain material communal means for the “mystical messages” to manifest, to be heard, and to resonate and expand?

Two thinkers come to mind in this regard. The first is Bifo Berardi. He distinguishes “connective intelligence” from “collective intelligence.” By the first, he means a kind of noosphere that is “programmed, machinic, computational, striated.” The internet is a prime example. Berardi thinks that the connective intelligence is like a dictatorship that slowly encroaches on every aspect of our lives, until we have lost some crucial feature of our humanity. “The body of the connective generation is stiffening in loneliness,” he says. He opposes this state of affairs to the togetherness and solidarity of the “collective.” He even goes as far as to insist that collective intelligence is the very precondition for any future worth living.

The second thinker is the American anarchist Murray Bookchin. He criticized the young anarchists of the 1960s, referring to them as mere “lifestyle” anarchists. The era of mass anarchism had, of course, ended in a seemingly irreversible catastrophe at the end of the Spanish Civil War in 1939. With mass organization, anarchism had had a real chance of becoming a widespread social formation. According to Bookchin with the onset of “lifestyle” anarchism that possibility was lost. I think that Bookchin’s contention is even more apt today than it was in his time. That is, one of the central features of the neoliberal regime we live under is the atomization of the self. (Think of Margaret Thatcher’s motto: “There is no society.”) The more atomized we become as subjects, the more isolated and, hence, more manipulable and vulnerable we become. In such an environment, anarchism is de-potentialized, and “anarchism” rendered yet another item available in the vast market of identity commodities.

What does all of this have to do with a potential contemporary or future mysticism? This may be the old-fashioned American pragmatist in me, but I believe that certain elements are essential for mysticism to have real, material, force in the world. These elements include the following: collective formations wherein people gather together on a regular basis; a coherent program of inquiry; a ritualized practice, done on a regular (daily?) basis; cultural elements, such as music and poetry, perhaps drama. I will leave the details for now. But I should mention that if this sounds like church or religion, the point is, for me, not to destroy certain forms that have endured through the ages, but to render them otherwise. Where to begin? By building “collective intelligence” institutions on the very brink—where solid ground meets the creeping edge of chaos.

Toward what end would such formations exist? Toward utopia, of course! They would exist in the spirit, if not overt actions, of revolutionary mystics like Thomas Müntzer. They would foster subjects who, in their words, actions, creations, and very manner of being, effectively destroy the forces of order and conformity. Contemporary mystics, in this sense, are not (merely) quietist contemplators. Thoroughly in and for the world, they are simultaneously in struggle against the world. And, like all effective worldly agents, they must engage in a serious anthropotechnic. I believe that the first question of order for any contemporary mysticism is, adapting Laruelle’s formulation: how do we render ourselves fit for the clash with Hell?

HS: So in a nutshell the “huge question” is: how can mysticism go beyond a mere “lifestyle” of “connection” which only remains trapped within a fancy individualism? How can mysticism be “collective”?

First, let us be clear that by the term “collective” we do not mean collectives of the communist type, I mean a certain ideology which suppresses individual differences in the name of a greater goal, of a secularized God, of some abstract ideal of equality. The individualism of Stirner, of Nietzsche, of Sartre was a really great idea until neoliberalism turned it all over again. And still, we learn from feminism that the personal is political. But again, under which conditions is the personal political?

The basic units I would like to start with are composed of 3-7? individuals: micropolitical collectives or packs. In these packs, there may be alpha wolves at times, but in the long run any hierarchies are too fragile to be maintained. For example, I am part of an art collective of three adults and one child; the three of us do always fight because we disagree on everything—haha!—but these constant quarrels lead to a very fruitful dialectics, since at heart there is an unspoken agreement on some basic dreams (not principles!).

Of course, such small collectives, project spaces, grassroots initiatives are unable to have a real impact on macropolitical scales and today there is a growing need for networks to connect them (or collect them?). However, the proposals I have seen thus far are mostly institutions which unite the vast diversity of grassroots groups under a colorful umbrella which brings about the good old problems of authority: a new transcendence where pure immanence is needed. How are we to conceive of a network which would be wholly immanent? Following the axioms of (a) rhizome by Deleuze and Guattari, the umbrella should be part of the network itself: a grassroots group and not an institution. Another axiom puts it more radically: “always n-1.” How could there be a network without an organizing Network, without a specialized collective which is solely dedicated to “networking”? An underground network which is solely composed of its parts, without the slightest trace of an umbrella?

When talking about politics and self-organised systems, immediately comes to mind the uprising at Wall Street, the revolution in Cairo: it often has been noted that these protests were without a leader, like spontaneous, energetic waves rather than a planned rebellion. I was there at Tahrir Square in the aftermath of the Egyptian revolution. What I can tell is that these theories make sense, there was not any sign of any leader. Nevertheless, today we know that the revolution slipped into moderate Islamism, and then a massacre which led to military rule again.

I wouldn’t say that the Egyptian revolution was a bad idea in any sense. I only say that protests are not sustainable in the long run. And in the Western world it turns to the opposite extreme: how could a protest have a real impact if it is appointed legal by the authorities? If it could harm them, it would be illegal.

A revolution is a great event and it is interesting to see that European philosophy inspired by the 20th century all culminates in the event (Ereignis, l’événement). But it also makes much sense that cultivated anarchists today have turned toward more sustainable ways of contributing to the ongoing cultural revolution—or should I call it “(r)evolution”?—which currently is witnessing an unprecedented transformation towards ecological awareness. Following eco-feminist philosopher Maria Puig de la Bellacasa, what counts in environmental ethics (not morality!) are not the big events, but changing our habits in the everyday.

So I agree that cultural spaces should commit themselves to “a ritualized practice, done on a regular (daily?) basis”. Instead of further dubious oppositions, they constitute dynamic holes or “oases” which slowly undermine the system from within. Most promising, I feel, are semi-institutional/semi-autonomous initiatives and collectives which due to their resources have a strong impact on the meso-level while maintaining a certain freedom of expression. Micropolitical collectives are the hotspots of the most mind-blowing ideas but due to their precarity and the empty promise of institutional support, these ideas are “captured” without any compensation. If these ideas could have any real impact on the macro-level is still written in the stars.

What has all of this to do with mysticism? In times of the Beguines, the answer would be close at hand. Today, we’ll have to reconfigure many things. At least, we can propose (via thought) a liaison of mysticism and anarchism which goes beyond the mere rejection of authority.

The rejection of authority (an-archy) only ever functions in a negative relation, whereas the concept of chaos would be entirely affirmative. However, I’m unsure whether the primacy of chaos is an axiom. Such would be the case if we take a Laruellean stance on Meillassoux who—in the tradition of Descartes—begins his argument with an “anhypothetical principle” (the necessity of contingency) in order to “demonstrate” the primacy of chaos. This “anhypothetical principle” is already a “philosophical decision” in the sense of Laruelle which—at best—aligns itself to some form of axiomatics. Meillassoux derives from absolute contingency, that nothing else is necessary and then attempts to derive some further “figures” such as the principle of noncontradiction. As much as I agree with the said primacy of chaos, to my mind in Meillassoux it is an anarchy with guarantee ensuring that no other principle—besides the principle of factiality—can rule about the world. Here chaos is the highest of all concepts from which the world may be derived. That’s why it was required in the first place to demonstrate its absolute necessity.

Chaos, in my view, is neither a concept nor a principle. Its primacy cannot be demonstrated and nothing be derived from it. To understand this view so radically opposed to that of Meillassoux, we have to differentiate between the necessary and the absolute: the absolute is unrestricted, whereas the necessary only follows from the axioms: chaos is the absolute, but not the necessary. Put this way, my view on chaos comes closer to the work of Laruelle: what I call chaos, he calls the Real or the One. Every axiom, in return, opens up a colorful umbrella of necessities, whereas chaos remains unrestricted and “foreclosed.”

What philosophical mysticism (or non-philosophy) can offer to inciteful anarchists, is a “worldview,” not only of a world without big boss, not even of a world ruled by chaos, but of a world which is chaos in itself, thus making sense of all the madness of authority, but also of a different kind of madness: the venture to live otherwise. Far from the dichotomy of order and disorder, chaos is the very place where all dichotomies emerge and crash on a giant heap of trash, where all authority arises and dissolves. Neither a concept nor a principle, but the very place where all the principles and concepts are inscribed. Chaos is unthinkable, and thus the very base for any thought.

Considering the vast environmental turn in contemporary art, I now realize that ayahuasca has become a central aspect not only of my life but also of my thinking as it merges chaos, on the one hand, with animism, on the other. As Viveiros de Castro insightfully describes, Amazonian metaphysics actually does differentiate between a pair of “nature” and “culture”: the crucial difference is that non-human beings are considered members of society while their different bodies are mere envelopes or “clothing.” “In sum, animals are people, or see themselves as persons.”

Of course, you may consider such a “worldview” as a childish game but then consider where all the adult “worldviews” have led us. As Manuela Zechner notes:*

children’s expressions of care often concern plant and animal life and welfare, ascribing subjectivity to living things that are not just human: this sensitivity of children, this ‘animism’ that adults try so hard to exorcise from them, is a crucial element for ecological change.

Deleuze and Guattari propose the becoming-animal of humans, whereas Viveiros de Castro suggests the becoming-human of animals, but I believe that both directions are fertile for eco-social transformation if committed to the art of playful fabulation. Especially in the Western context which seems to lack a traditional account of environmental consciousness, the playfulness of art is crucial to evoke—through technoshamanistic fabulation—ritualistic practices which propose a radically inclusive coexistence with non-human kin to the contemporary world.

So if you ask how mysticism can be more “collective,” we also have to re-consider which kind of collectivities we talk about. After all, even the talk of “packs” is not only metaphorical.

(* I want to thank my partner in crime Evgenia Giannopoulou here for introducing me to Zechner’s work and the related themes of collective care and eco-social transformation.)

Furious Practice, Ruined Utopias

GW: My gut feeling is that, with your response, we have arrived at the beginning of the end of our discussion. (The end, indeed, can take forever to reach!) Why do I say this? Because you have laid out a programmatic path forward. Of course, the details of the “daily practice” still require precise formulation. But with your statement, I feel, the rationale is complete. I think, too, that your criticism of Meillassoux here is necessary and even crucial to our ends. You say, “Chaos, in my view, is neither a concept nor a principle. Its primacy cannot be demonstrated and nothing be derived from it.” Yes! A Laruellen “first name of the Real”—foreclosed to elaboration but from which we might act. We can, of course, discuss “it” interminably. But “it” would not be chaos, would not be the Real. Rather, “it” would be “chaos,” “the Real,” with the necessary distancing scare quotes. Since we are dealing here with “neither a concept nor a principle,” the question becomes, for me, what is a practice worthy of the name “contemporary mysticism”? As you say, I think a rehabilitated notion of “the individual” is necessary here. The question of whether we westerners can adopt or adapt non-Western—Amazonian, Asian, and so on—modes of practice and being is, for me, an open but complicated issue. And by “can” I mean are we even capable of it, is it even feasible, realistic, possible to do so? The question looms: what, specifically, would a contemporary mystical practice entail?

So, we could fruitfully pause here, take a breath, and then pivot afresh toward the vast sphere of practice that lies before us. But first I should ask you if this is where you think we now stand—at the cusp of practice? And if not, where do we go now?

HS: Thank you, Glenn. Recently, I listened to the Imperfect Buddha Podcast entitled “Glenn Wallis on Personal Practice and Anarchism.” The podcast starts off with heartful, roaring laughter and to me this is the core of any kind of contemporary practice. Who hasn’t felt the pious seriousness of some New Age style ritual and just wanted to laugh and shout: “please get me out of here,” haha!

All systems of belief—and all the more of practice—must be endowed with a sober mind of disbelief or even absurdism. But under this condition, everything goes: from astrology, to yoga, to prayer, to sex, to the most obscure ceremonies for each and everyone according to their personal tastes. Mysticism—after all—is the greatest celebration of our overall existence in this world and it would simply be so bad to spoil it with ideological concerns. All rivers flow into the ocean and the greatest wisdom—after all—is to laugh about ourselves.

In the mentioned podcast you proclaim that the danger of ideology may be avoided by making it explicit, but following my experience, explication often steals the show and ruins the ecstatic flow of any kind of practice. What are your thoughts on explication nowadays and can you conceive of different techniques of practice for furious, free minds?

GW: I think that it is for the kinds of reasons you mention that laughter is so central in Nietzsche’s thought. He dislikes the gurus—the “improvers of humankind”—precisely because they are so damn heavy. Being heavy, they always tend downwards. (In fact, the Sanskrit word guru is cognate with English gravity.) About explication, I think it is useful for unmasking what tries to remain hidden. One of my lifelong interests is ritual. An ever-present concern in analyzing the power mechanism bearing on a ritualized practice is expressed in the saying: “Power is not manipulative; but hidden power is.” Power, of course, can take many forms—relational, social, institutional, and so on. How does a particular ritual encode, create, articulate, perpetuate, challenge, etc., etc., such power? I believe that the same can be said for an ideology. So, explication is the practice of making known that which of necessity must remain hidden in order to preserve the (ritually, ideologically, institutionally) desired power dynamic. Beyond that, well, explicit, function, I agree with you. I, too, want to preserve and enable ecstatic flow. To me, this requires, as you suggest, a high degree of impressionism. However, a degree of explicitness would also play a role. And with your final question, I feel we have hit practice payload.

I love the “furious, free minds” condition. If I were a proselytizer setting out to build a community of contemporary mystics, I would do roughly as follows. First, create a textual expression of the aims and goals and assumptions in play. Not too much explanation; just enough to suggest some parameters. This text would include a description of a practice. The practice would involve dialogue around the root text, but extend far beyond, in the spirit of Jacques Rancière’s notion that “Everything is in everything; learn something and relate it to all the rest.” Maybe some formal contemplative meditation could be included. Personally, I find concentration technique profoundly valuable. It could be rationalized as a feature of practice in that it involves a countercurrent to unobserved consciousness. Maybe. Then, I would create the community space where interested practitioners could gather and get to work…or play.

A formation like this could, of course, be filled in with countless details—explication. Since one of its guiding values is the virtue of “furious, free minds,” the formation must of necessity remain open, expressionistic. A challenging question for a mystical practice like the one we seem to be stumbling towards is how to permit experimentation and individuality within the bounds of a practice.

HS: Well, you keep on talking about practice like Plato who imagined the utopian state, while in the everyday you actually run an experimental platform for “rigorous & rebellious learning” called Incite Seminars. I’ve been part of your journey for some months now and I must say that “experimentation and individuality within the bounds of a practice” is already happening right before our eyes.

Utopian thought and practice, in this context, gains a wholly different meaning; it is far removed from ideology or any wishful thinking. To the contrary, it enacts the future in the now, despite the ongoing return of fascist ideologies worldwide that we’re still witnessing today. Our conversation was overshadowed by the US election and the death of François Laruelle. While the latter marks a time of grief for contemporary thought against authority, the former was not even a surprise. Mysticism is not only ruined but it also takes the form of absolute refusal. Utopian thought and practice must take place inside the folds and cracks of that very system; it is the wildflowers and weeds that grow in the ruins of this planet.

In contrast to a common misconception, mysticism is all light due to the darkness that surrounds it. My initial question “What is contemporary mysticism?” not only summons forth the specters of the past, but it evokes the future in the present. Would this be the kind of utopia that Laruelle envisioned?

GW: A beautiful summary of our conversation, Hannes! For my final remark, I want to say something about enacting the future in the now, as you put it. I think you are right to see Incite Seminars as a practice orientation. The first thing you see when you enter our member space is this comment from The Production of Space by Henri Lefebvre: “‘Change life! Change society!’ These precepts mean nothing without the production of an appropriate space…New social relationships call for a new space, and vice versa.” Given your creation of Freigeist Verlag and co-creation of Chaosmos, you yourself surely know and feel the necessity of a new space for the encitement of something new, or at least of something otherwise.

I like to think of such spaces as instances of what, to me, lies at the very heart of a contemporary mystical practice. I am thinking of the ancient idea on which the first western teaching and learning academies were founded by the ancient Greek philosophers. That idea was the epoché. It persisted through the Renaissance and into the modern world in the form of the university as communitas, a shared community of teachers and learners. In the current age of omnipresent neoliberal corporatization, the university as epoché has decayed beyond repair. (Hence, the folds and cracks that you mention.) In short, the epoché is a space in which the needs of commerce and power are bracketed out in order to let in concern for the world. I know that sounds ridiculously vague. But the question of exactly what such concern might entail is the very animating spirit of the teaching-learning-practice space that is the epoché. Peter Sloterdijk says that the epoché was “an asylum for the mysterious guests that we call ideas.” Ideas are mysterious guests because, in the epoché, they arise like vapor out of the cauldron of communal reflection. But I understand the mysteriousness of ideas to lie mainly in the fact that ideas — these ephemeral, spectral, wisps of virtually nothing — are potential forces of concrete processes.

François Laruelle’s idea of the “force (of) thought” is helpful here. In simple terms, this means that an idea only matters, it only has real-world force, once it is put into practice. An idea in practice becomes the basic stuff of subjectivity, community, society, action, world. An idea lived is brutally concrete. So, a quick alchemical summary: the stewed-cauldron of the epoché conjures vapor-ideas that animate mutable-subjects that transmute the world-as-concrete-utopia.

In an age of despair like our own, I hope others will develop practices of “concrete utopia.” “Concrete utopia” is the name for an organizational process. It makes an intentional play on the Latin term concrescere, “to grow together.” Concrete utopia signifies a material growth, or a growth with and out of our present material conditions. For this reason, it is different from the idealized utopias found in literature, beginning with Thomas More’s Utopia. “Concrete utopia,” by contrast, is a dynamic practice that “contains within it the forward surge of an achievement which can be anticipated,” as Ernst Bloch, the originator of the concept, puts it. As someone banished by his fellow East German Marxists as an irredeemable heretic, Bloch is, for us today I believe, a model practitioner.

The title of Bloch’s eccentric, majestic, somewhat apocalyptic three-volume book provides a clue as to the aim of a concrete utopia: The Principle of Hope. “It is a question of learning hope,“ Bloch begins. For those of us working in the contemporary mystical epoché, hope is not a spontaneous emotional quality; it is not an affect or element of belief. Hope, rather, is a species of action, one which “requires people who throw themselves actively into what is becoming.” Hope is a condition that must be learned.

I’m not sure why Bloch is coming so strongly to mind at the moment. Maybe it has something to do with the election of Trump and the death of Laruelle. Those two events certainly spur me, yet again, to think hard and with urgency about, well, the vagaries of concerned action in an intractable, uncaring world. You and I come just now to the struggle, Hannes. But how many have come before, and how many will follow? Those who dwell in the asylum of mystery must wonder if the one irrefutable truth that they have glimpsed, the one true mystery that they have uncovered, is simply the fact of the lawless, uncontainable chaos at the heart of the World. “We are in the world,” Samuel Beckett reminds us, “and there is no cure for that.”

Well, yet here we are, in the world.

Finally, can we take to heart this transmuted statement about non-philosophy by Laruelle (from “A New Presentation of Non-Philosophy.”)?

I see [contemporary mystics] in several different ways. I see them, inevitably, as subjects of the university, as is required by worldly life, but above all as related to three fundamental human types. They are related to the analyst and the political militant, obviously, since [contemporary mysticism] is close to psychoanalysis and Marxism [and anarchism] — it transforms the subject by transforming instances of [mysticism]. But they are also related to what I would call the “spiritual” type — which it is imperative not to confuse with “spiritualist.” The spiritual are not spiritualists. They are the great destroyers of the forces of [religion] and the state, which band together in the name of order and conformity. The spiritual haunt the margins of philosophy, Gnosticism, mysticism, and even of institutional religion and politics. The spiritual are not just abstract, quietist mystics; they are for the world. This is why a quiet discipline is not sufficient, because man is implicated in the world as the presupposed that determines it. Thus, [contemporary mysticism] is also related to Gnosticism and science-fiction; it answers their fundamental question — which is not at all [mysticism’s] primary concern — “Should humanity be saved? And how?” And it is also close to spiritual revolutionaries such as Müntzer and certain mystics who skirted heresy. When all is said and done, is [contemporary mysticism] anything other than the chance for an effective utopia?”

_________________

Authors’ Bios

Having lived and studied all around the world, Hannes Schumacher works at the threshold between philosophy and art. He has worked intensively on Hegel and Deleuze, and he has also published widely on Nishida, Nāgārjuna, chaos theory, global mysticism, and contemporary art. Hannes is the founder of the Berlin-based publisher Freigeist Verlag, co-founder of the grassroots art space Chaosmos ∞ in Athens, and lecturer at Incite Seminars in Philadelphia.

Glenn Wallis is the author of several books, including Cruel Theory/Sublime Practice and A Critique of Western Buddhism: Ruins of the Buddhist Real, as well as numerous articles, chapters, and essays on various aspects of Buddhism, education, and mysticism. He is the founder of the blog Speculative Non-Buddhism and of Incite Seminars. His most recent books are An Anarchist’s Manifesto, Non-Buddhist Mysticism: Performing Primitive and Irreducible Presence, and Nietzsche Now!. You can read more about him at his personal website.